Interaction Design in the Wild - Sonia Zhang's Portfolio

I am an anthropology student trying to make sense of interaction design for animals.

Week 7 - Zoo Visit

by Sonia

As a part of our course, in the morning on March 2 (Saturday), our class went to Central Park Zoo with a guided tour offered by an enrichment supervisor.

It was snowing the night before and snow was visible everywhere at the zoo - we were told that this acts as a part of sensory enrichment and they use a lot of snow for enrichment purposes for various species!

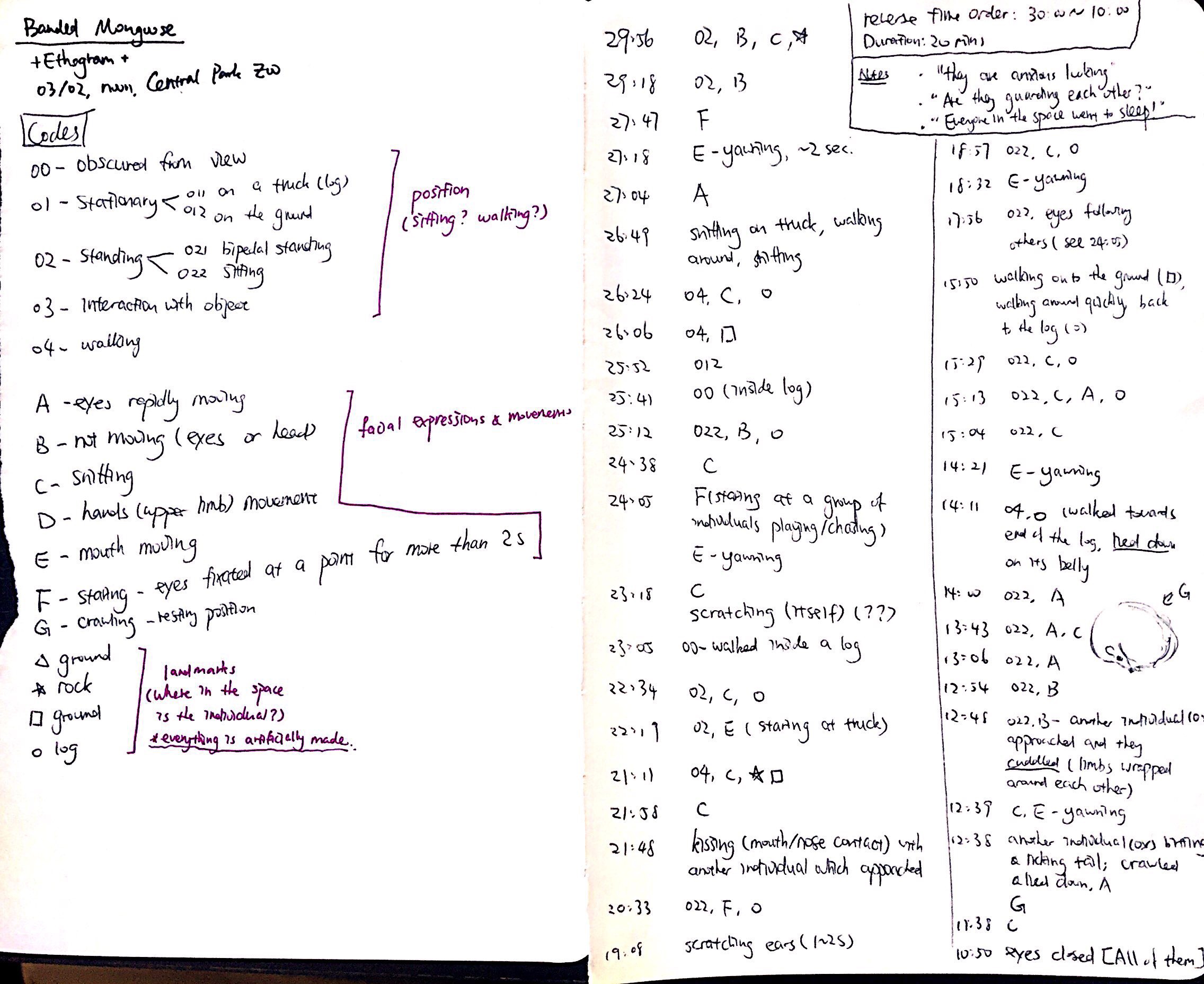

Ethogram

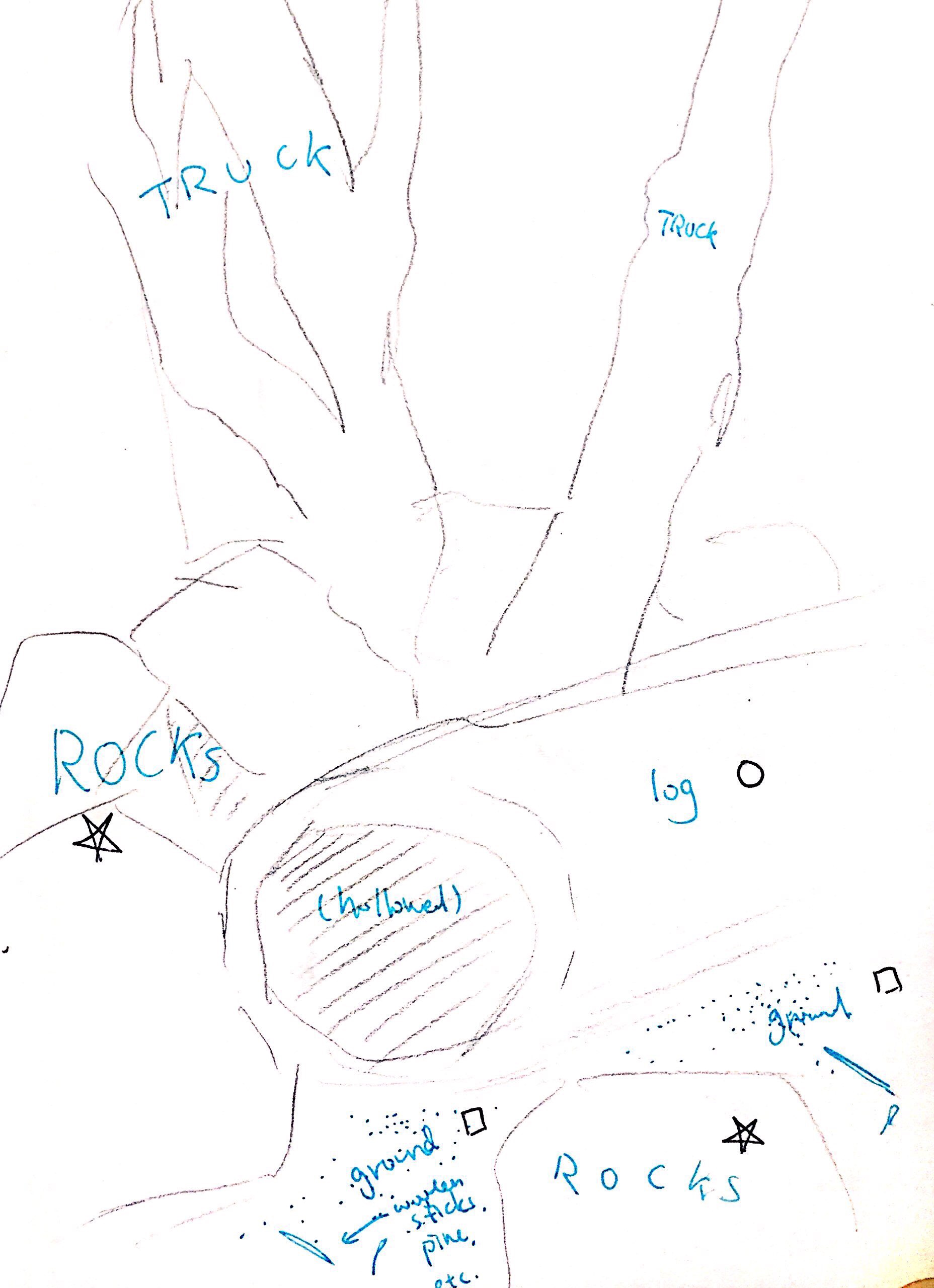

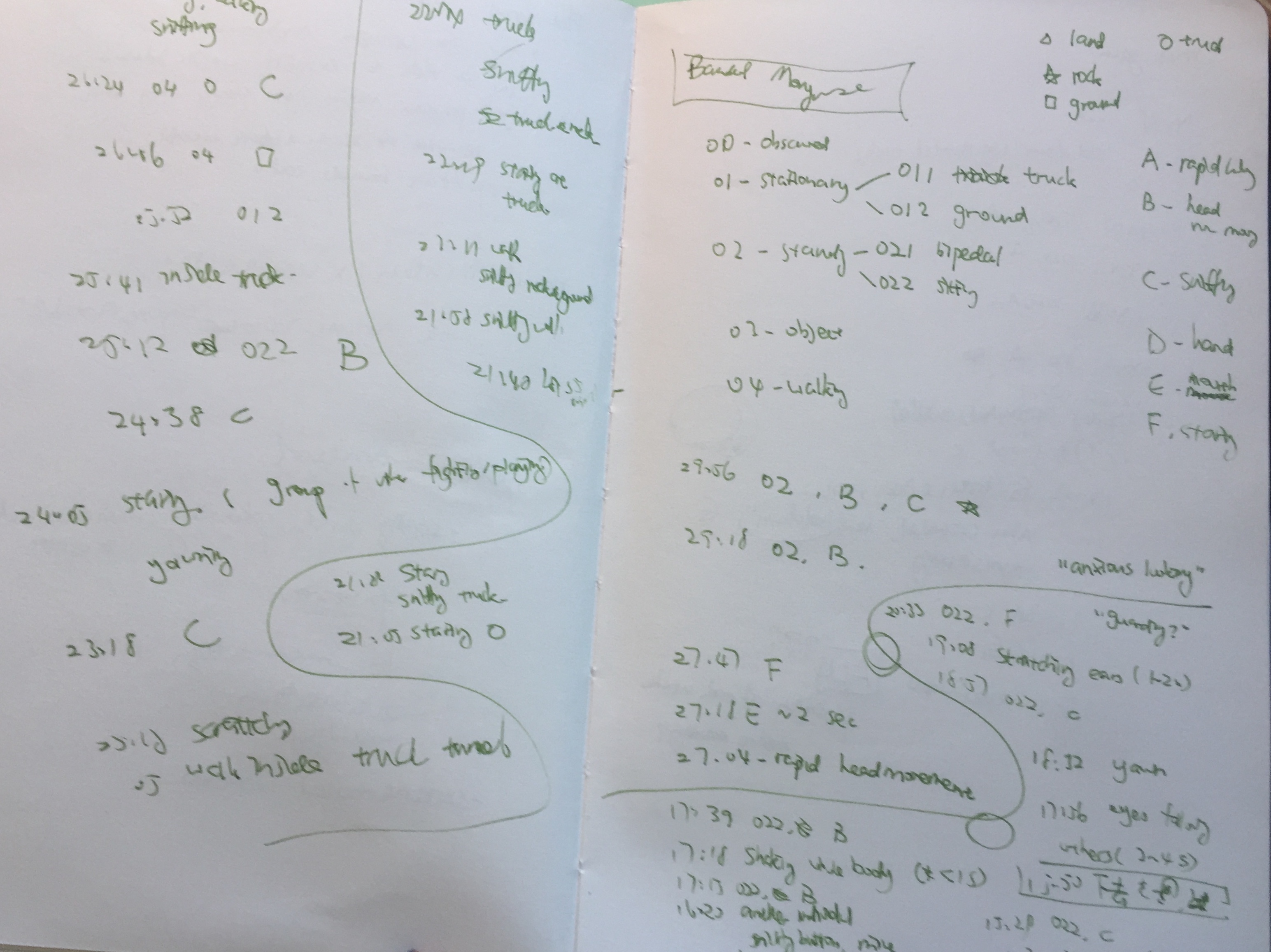

After this visit, I had my second attempt at ethograms. After the complete failures from my first experience of ethogram with cranes, this time I have my group project partner Yufei Zhang who decided we should work on the same animal. We decided to visit the banded mangoose (Mungos mungo) in which a space all made of completely artificial artefacts with some placed pine cones, something introduced for enrichment purposes albeit not part of their natural habitat. There were 6-7 individuals within the space. See a photo of the space with a brief sketch of landmarks I used for my ethogram below:

This time, instead of starting from scratch and recording everything, I did some preliminary observation for the first 5 minutes and came up with a code plan, each representing a certain behaviour (in categories “position” “facial expression&movement” “landmark”). This is inspired from the ZooMonitor App, however, I found more ease with this one because when I discovered new categories of behaviours, I could just create another code by writing it down on the paper, instead of quitting the app, add a new category, and start a new observation program.

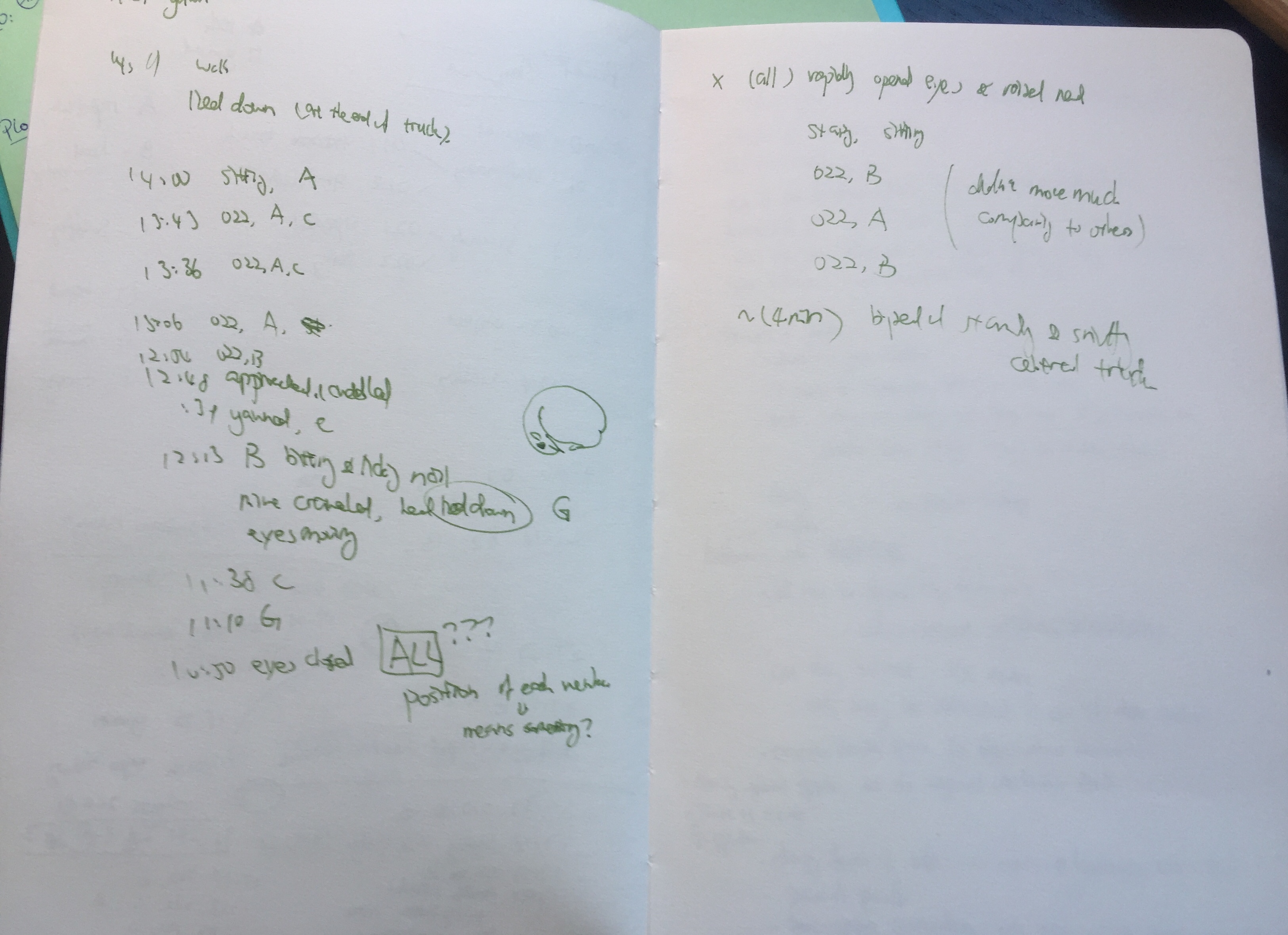

Look at my ethogram, compiled from real-time notes into a more organised ethogram:

Interesting findings:

- Ethogram techniques:

- having codes made my ethogram much more organised and comprehensible, and I was able to quickly denote common behaviours by codes, so that when a special behaviour occured, I could focus on recording verbal information on those new elements. It was very important under the limited time I got when behaviours were constantly switching.

- The ability to incorporate new codes also made it easy for me to refer to previous similar behaviours throughout my recording (e.g. yawning and rapid walking occurred multiple times; if I had not coded them I might record each entry as a new behaviour without recognising its repetitions).

- Although I miss the details I had in my first ethogram, I would say the overall amount of information captured and the openness for subsequent analysis (frequency of certain behaviours, spatial distribution) are more successful in this ethogram.

Group work (among humans & animals)

-

Yufei and I each focused on one individual of the group; turns out that his individual were one of the active, running-around ones while mine was sitting and sniffing for most of the time. The two formed stark contrasts in their behaviour patterns, and made us wonder if this reflects a certain division of labour (Yufei: are the ones on the rock guarding the ones that are playing?). We might not have thought of this if we only attended to one individual.

-

I still find the incorporation of group dynamics difficult when I focus on one individual; when another approached and they interacted (wrapping their limbs around each other, “kissing”, licking, etc.), I had too little time to make codes for distinguishing one’s behaviour from another.

-

An interesting phenomenon occurred towards the end of our observation: individuals that were having different behaviours, some running, some sniffing, some stationary, all started to sit down and settle: some “cuddled” with each other, some occupying a rock, their eyes half closed. Then within a very short (less than 30 seconds) time, their eyes all closed, as if they collectively started to take a nap. The “nap” lasted for about 6 minutes (we were too excited to keep track of time and take notes), then all woke up and returned to activeness at roughly the same time. This highly synchronised switch of behaviour convinced us that their behaviours are mediated by some dynamics, possibly involving communication, by the entire group. They are social animals.

At a certai instance all the individuals crawled up and went to sleep.

Monunculus?

Our last task is to draw a cartoon-ish sensory magnification of the animal we observed. I chose to magnify their nose and front limbs since they exhibited the most movement in my observation, however, I have to be aware that I based this on my visual observation for a very short time period, and since I have no access to the sound inside the space, I had no info on how much information might have been processed with their auditory systems; my only cue was that their ears did not move, which is a poor proxy.