Interaction Design in the Wild - Sonia Zhang's Portfolio

I am an anthropology student trying to make sense of interaction design for animals.

Week 3 Observation and Ethogram

by Sonia

“There are other worlds around us. Too often, we pass through them unknowing, seeing but blind, hearing but deaf, touching but not feeling, contained by the limits of our senses, the banality of our imaginations, our Ptolemaic certitudes.”

Hugh Raffles, Insectopedia.

+ Ethogram 1: Central Park Zoo, Crane +

Date: Sunday 02 Feb, 11: 49 - 12: 19

Apparatus: Pen-and-Paper (+ a clip board)

First, have a look at my ethogram. I thought to reconstruct it into a neat manner but this is worth reflecting on.

I understand this does not make any sense, and looks no where close to the tabularised form with detailed descriptions as our assignment examples show.

Because it did not make any sense to me either. It was a complete farce - I did not know where to start from. I did not know where they were looking at; their eyes were situated at the two sides of their face. I couldn’t distinguish the complexity of their constant self-grooming. I couldn’t find a word to describe how their necks curled in amazing angles. I ran out of time for recording new surprising behaviours so my hand writing became incredibly messy. Their movements are so rapid and incomprehensible, whereas hand-writing ethograms without predetermined categories invites infinite descriptions beyond the practitioner’s capacities. Hence the running out of control, the panick and the resulting table.

I also constantly hoped that I have had helpers around me, so there could be a division of labour and each could focus on a particular kind of movement. One recording eye movement. One taking photos and videos of typical behaviours so they can be described better in retrospect. One focusing on recording times of behaviour occurrences. And so on.

I believe the mechanistic ideal type of an ethogram fosters a sense of division of labour in the recording process, a mode of production in contradiction to my pen-and-paper, untabularised approach. My messy diagram in fact helps me recall the details of my observation based on my own memories, cues from those quick sketches, my choice of language…but it is not the purpose of an ethogram. Making an exhaustive behaviour record for myself is far from enough.

What perplexed me the most is how to take interaction into account with ethograms. I feel forced to focus on one individual, not just because of using paper-and-pen but also because one is enough to keep my mind occupied. There were few discernible interactions between the 2 cranes, however, they clearly reacted to people who comes and goes, the movement of other species of birds calling around them, and the sounds and textures I failed to capture. How do I take in this multitude of reactions and interactions? Taking the entanglement with other actors risks an exhaustive addition of ambiguity, posing significant challenges to the ethogram framework.

How to incorporate ambiguity into an ethogram where everything seems to be clearly defined and delineated?

What would I do differently, and what would I change?

- I would come up with a predetermined table of behaviour categories with detailed descriptions. This has to be done with prior observation without presuppositions.

- I would make abbreviations for each behaviours for faster note taking.

- In terms of helpers, if I could I could have programmed something to track, let’s say eye movement of the crane. I wish I have the technical proficiency for this.

- I would also include more sensory categories of the observation - during the freezing 30 minutes I did not just see with my eyes. I heard noise, I smelt scents, and I tried to imagine what else would a crane feel. They should all be parts of an observation project.

My two behavioural experts:

- Krajewski, C.; Sipiorski, J.T.; Anderson, F.E. (2010). “Mitochondrial genome sequences and the phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae)”. Auk. 127 (2): 440–452. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09045.

- This presents a classical evolutionary approach to make sense of cranes, by placing them in a polygyny with other animal species using mitochondrial genome analysis.

- Higuchi, H., Ozaki, K., Fujita, G., Minton, J., Ueta, M., Soma, M., & Mita, N. (1996). Satellite tracking of White‐naped Crane migration and the importance of the Korean Demilitarized Zone. Conservation Biology, 10(3), 806-812.

- This studying is different from (1) in an interesting way because this one seeks to discern the patterns of crane behaviours, particularly on migratory events. It relates to broader concerns in conservation and triggers discussions on human’s handling of their relationships with animals. Consequently, it does not take relationships with other species into account.

+ Ethogram 2: San Diego Zoo Polar Live Camera, Polar Bear +

Date: Sunday 02 Feb, 18:42 - 19:12

Apparatus: ZooMonitor

I spent at least 2 hours in total trying to come up with a good prior categorisation of my ethogram using ZooMonitor; I followed my reflection from Ethogram 1 and tried to use some prior live cam observation to define categories too.

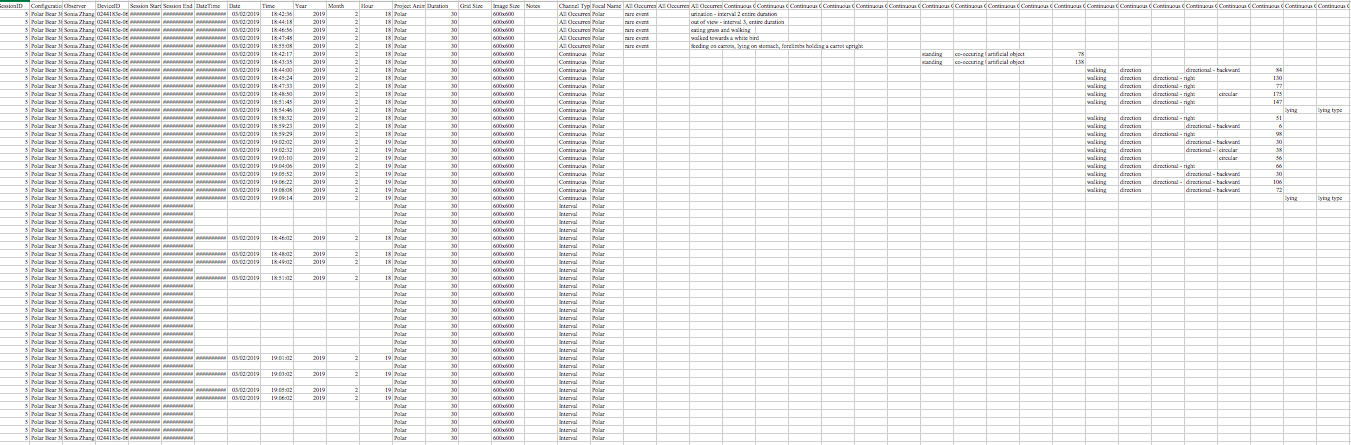

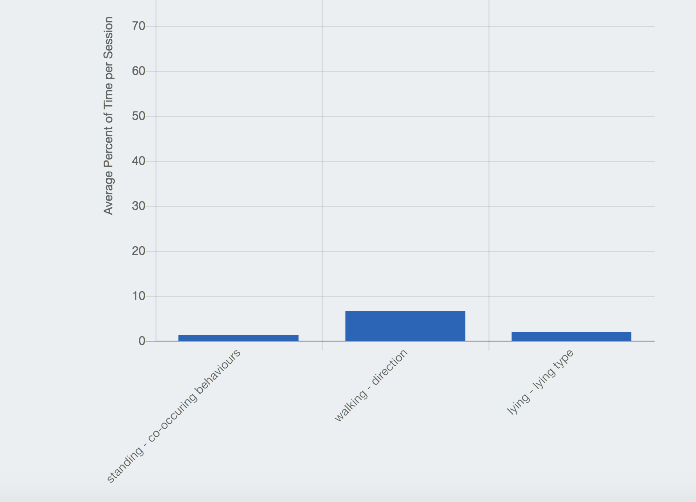

However, the result is a complete mess of tables that I do not understand:

I was struggling with the fact that I only had the choice to click on my boxes of categories without the option to take textual notes of each recordings. The graphics in Ethogram 1 which helped me intuitively make sense of the behaviours was not an option either. This calls for a more defined process of categorisation and reflects a need for simplicity, standardisation, and I would say, dehumanisation.

At the same time, using ZooMonitor as a highly regulated ethogram creating device makes me wonder to what extent does the use of ethogram inherently render a mechanistic view of animals. This way of recording necessarily translates an animal’s behaviours into small, precise building blocks of actions, measured by intensity, frequency, interval, etc. My frustration with not being able to add textual information also comes from how I think a lot of texture from the behavioural repertoire of the animal is lost in this ethogram creating technique, this particular technology of thinking.

Watching animals from a live camera also limited my level of engagement in the observation, as only visual engagement was available and I did not have the choice of where to look at. However, with the aid of technology I assume this is a helpful way of tracking visual trajectories, and this merit should not be underestimated.

My two behavioural experts:

- Ramsay, M. A., & Stirling, I. (1988). Reproductive biology and ecology of female polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Journal of Zoology, 214(4), 601-633.

- This study investigates the relationships between female polar bears’ reproductive behaviours and their environments by closely tracking their lives in an ethological setting, together with a degree of human intervention for identification. This predominantly ethological approach is interesting and insights on how polar bears behave might be learnt.

- Amstrup, S. C., & DeMaster, D. P. (2003). Polar bear, Ursus maritimus. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and conservation, 2, 587-610.

- This encyclopedic description of polar bears’ evolution, development and behaviours is exhaustive and comprehensive, in which traces of Tinbergen’s all four questions can be found. According to the article, “Dr. Amstrup has been conducting research on all aspects of polar bear ecology in the Beaufort Sea for 24 years”.

+ Conclusion +

My two attempts of generating ethograms this week can both be described as failures. I thought I tried my best with following ZooMonitor’s protocols, I tried to keep track of my observations, I kept the balance regarding anthromorphism in mind. I thought this is a start to understand the world of animals, but I failed and failed. However, with these failures, my desire for connecting with my animals’ senses have become more intense than ever. It has become a genuine motivation to go beyond “the limits of our senses, the banality of our imaginations, our Ptolemaic certitudes”, and I am curious about whether these sentiments are useful at all, how can they be incorporated into the mechanistic framework of ethograms, and the data-oriented practices of design technology.