Interaction Design in the Wild - Sonia Zhang's Portfolio

I am an anthropology student trying to make sense of interaction design for animals.

Mid-Term Functional Prototype - II

by Sonia & Yufei

1. Conceptualisation

The original goal of our project was to design an artefact that engages with the curiosity of a specific species, common ravens, and the end goal is to achieve a sense of communication with the animal through back-and-forth interactions. In order to achieve this, our design is based on the following criteria:

- Mimicking a social, communicative other

- Artefact should be able to respond to animal interactions in distinctive, conspicuous ways

- Engagement should be multimodal and multi-sensational

- In order not to confuse it with goal-oriented training device, we tried to not include food rewards.

However, at the initial field testing phase we realised 1) common ravens are not very accessible in New York City; 2) placing the device where bird species around is insufficient for attracting attention, giving us no information for future iteration ideas.

To progress from pure conceptualisation to a feasible project, we are making two major conceptual changes: To expand our user from crows to all intelligent birds found in the urban wild. The most common ones are pigeons and sparrows. To include food resource as part of our device as a necessary step to attract initial attention and curiosity.

2. Research grounding

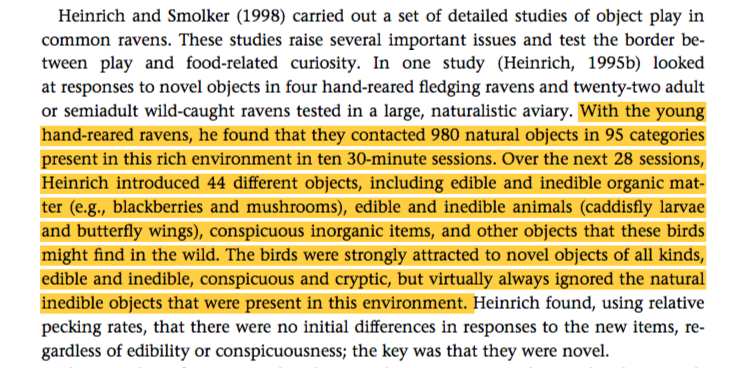

When we were investigating the project as an artefact designed specifically for the crow, a wealth of research has shown this species’ remarkable ability to engage and play with novel, not necessarily edible objects. This made us assume a degree of confidence for the bird’s likelihood to engage with our box.

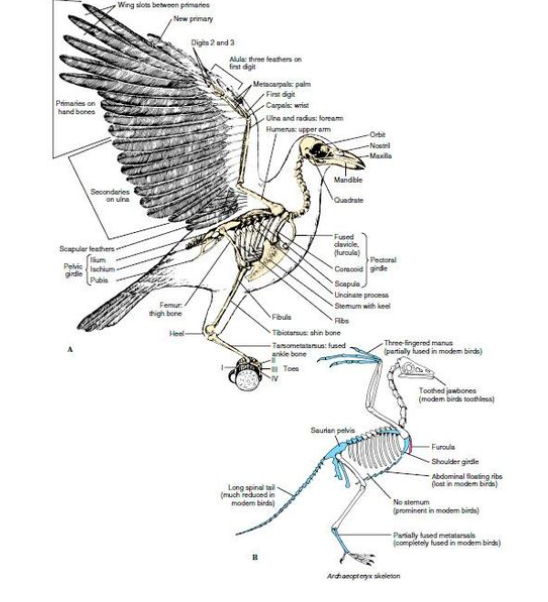

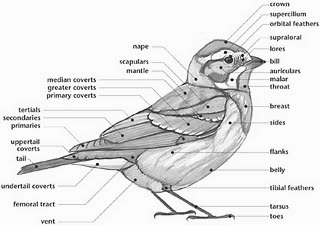

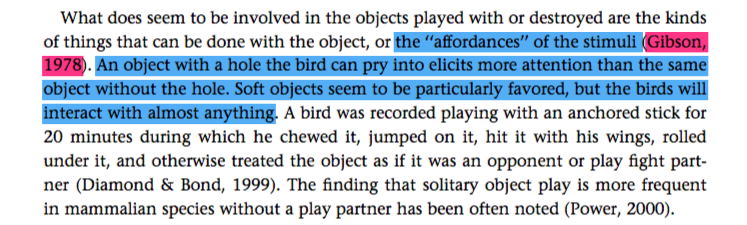

We also learnt that birds have a general liking towards shiny objects, soft textures and items with holes which they can fit their mouths in. Because of this, we made holes on our device specific to crows’ beak size.

However, after some initial observations, we realised the design of an engagement with the urban wild cannot be entirely drawn from scientific observations of animals in more remote wilderness. Furthermore, to take the evidence for bird intelligence, we should have kept in mind that birds may have culture and each social group might have a specific rule for interactions with objects. Thus field research, including behavioural testing without the artefact, conversations with people who regularly attend to the urban wild, are crucial.

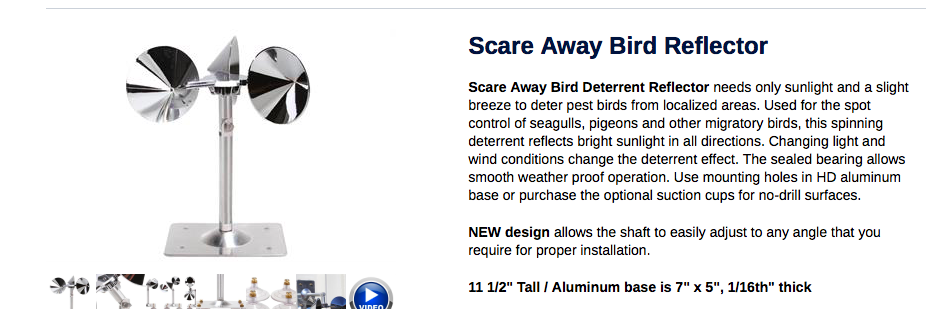

We consulted one bird lover, who were surprised to hear that the box in made shiny to attract birds. According to him, back at home farmers would hang strings of CDs, a shiny and reflective object, to the ceiling of their houses in order to scare birds away. This evidence directly contradicts the ones claimed by science literature, and reminds us not to take the latter for granted.

source https://www.nixalite.com/product/scare-away-bird-reflector?p=792&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIwI34hYig4QIVEITICh0VXQFsEAQYASABEgIBjvD_BwE

We were also reminded that while birds are curious, they are also extremely cautious and territorial. If they see a novel object, it takes time for familiarisation. This hints that the field tests and observations we have should take place at a much longer time-scale.

3. Explaining our device

Our curiosity box is a wooden box with a series of internal mechanistic devices. The internal structure is invisible to the user unless peaked from the several holes, but three soft patches with shiny stickers are made conspicuous, inviting the birds to peck and hence trigger the piezo sensors behind it.

Each piezo sensors connect with one servo motor, which are programmed differently and attached to distinct materials (fake feather, wooden sticks) to create a multitude of sounds and movements.

Another feature is a string which pokes out from one of the holes from the box, which is attached to a heavy object inside. The pulling of string with beak will cause the heavy object to move.

4. Video

In case the video doe not work, hereis the link.

Highlight:

- In the first setting, no birds approached the box but up to 10 sparrows approached the bush around it and made frequent, loud calls.

- For recording purposes, the box was then moved to an open area. Birds approached food nearby but did not approach the box, even though there were abundant food on top

- For a while we attracted a flock of pigeons through dropping food in a conspicuous way. From the video, it is evident that the pigeons attended to the food on the box, but nevertheless did not approach the box; their necks slightly shrink when heading the box, then turns around. Note at this time, the box makes randomised sound.

- At a moment all the pigeons and sparrows flew away and never came back. The incidence did not coincide with any external events (people approaching, loud noise), so it is probable that something about the box scared them.

5. Reflection and Future Iteration

There is a lot to reflect upon from this project. The field test has proved that designing from literature research alone is far from enough; iterative field testing and breaking down the process into smaller steps is important.

There are several sources we could consult and research beyond the academic level: browsing existing bird-related products, talk to bird pet owners, regular feeders of the urban wild are all important resources that we missed this time.

For example, we are suggested to not include the box at all in our initial field tests; instead, we should use food alone, experiment with different methods of food distribution, figure out the birds’ preferences, then alter the box so that it fits into the food delivery movement.

Similarly, we could have placed objects of different shapes, record animal reactions to them, then decide the morphology of the box.

Finally, the field tests should have been much longer (ours are 30 mins for each site). Humans have a distinct conception of time and space, and birds have their own process for familiarisation. If we could have given more time for the birds with the box, we might be able to record different interactions and provide new information for future iterations.