Interaction Design in the Wild - Sonia Zhang's Portfolio

I am an anthropology student trying to make sense of interaction design for animals.

Week 6 - Enrichment II

by Sonia

Blown in the wind, moistened by dew, their fragrance fills the canyon,

And sometimes pairs of white cranes arrive here on the wing.

Though secluded searching takes me far, I cannot reach the end,

Thus I intend to break from the world, and leave its confusion behind.

Xiu Ouyang 欧阳修 1051, translated in Ji vol. 1, 2.16.

Stage 1: Setting the Framework - What am I looking for?

What is enrichment? How to bring the concept forward to wilderness?

Animal enrichment vaguely refers to the enhancement of animal well-being in captive environments, a type of care that aims for more than ensuring physical survival. It is a value embedded in the spirit of humanitarianism, and confronts an array of ethical considerations and challenges. While they are important and worth more discussion, in this design project, I am more concerned with the question of why is enrichment an interesting concept to apply in wilderness, that is, to the life of animals who live in an environment without complete human control and management.

Here wilderness does not mean an illusory place where human is non-existent: it can refer to birds in the city, monkeys in a temple, buffalo cows in a natural reserve, etc. In my particular project, I am going to work with cranes, an animal that is marked by its sacredness in East Asian folklore and religions, observed by nature lovers with amazement, protected in wetland reserves, and also managed at zoos. While my research will be drawn from multiple species of cranes, my target species of my design would be white-naped cranes (Antigone vipio), which is mostly a practical choice because they are exhibited both at New York Central Park Zoo and San Diego Zoo.

Stage 2: Preliminary Research - How to understand then design?

Quick facts about crane life and behaviours:

- life span: 20-50 years

- habitat: wetlands and grasslands

- food: omnivorous — spanning from grasses, insects to aquatic life

- major behaviours studied:

- dancing (prosocial and playful behaviour)

- reproduction: courtship rituals, nesting, parental care

- migration

- signalling (communication systems)

- preening (common and time-consuming)

- roosting (highly regular behaviour according to sunrise and sunset)

What am I enriching? Why is it meaningful?

In my preliminary proposal, I was planning to either provide them with a “niche” or a “colour-changing block”. While the former seems too ambitious as the concept risks designing an entire ecosystem containing multiple artefacts, the latter cannot be justified because limited studies are done on cranes’ visual perceptions.

However, I still find the term “niche” useful, in this context referring to the collection of resources and competitors that are relevant to an individual’s material life. It is a more useful concept than environment and place, because several species can occupy different niches, and therefore avoid competition and resource overlap, within the same physical space. This can be achieved through specialising in specific food, using specific nesting materials, etc. Cranes are known as a flexible species which would alter their diets to take advantage of current resources - this makes me wonder whether they are also open to introduced living structures and spaces.

Taking a closer look to crane’s behavioural research and existing enrichment programs, a lot point out that despite being social and having a complex communication system, cranes are shy animals that prefer spaces for hiding, both at zoos and in wilderness.

For example, an enrichment attempt proves crowned cranes’ preference for hiding behind plantations:

The International Crane Foundation’s Black Crowned Cranes Djoudj (pronounced “Jude”) and Sahel with their “exhibit furniture,” or cut, dried prairie grasses in buckets of sand. Alyssa notes that the cranes “like to hide behind them and also pull the grasses out and toss them around. It’s one of their favourite activities, really.”

From savingcranes.org

A paper based on observation at wetland reserves in China reveal similar findings: among the six factors determining white-caped cranes’ habitat selection, two are related to safety — protection and concealment:

Adult white-naped cranes guard the nest and eggs during incubation and hatching…he height of remnant reeds (124.36±13.99 cm) was greater than the body height of incubating white-naped cranes. If a crane stretched its neck when sitting on the nest or stood on the nest, the reeds con- cealed both the nest and the incubating adult. Thus the density and height of remnant reeds were also favorable as protection for cranes during the nesting period. (p.950)

White-naped crane is sensitive to disturbances caused by man and domestic animals because of its timid nature, especially during incubation. To reduce extraneous disturbances and increase nesting success, nesting away from an interference region (2.05±0.12 km) was an adaptive strategy for white-naped cranes. (p.951)

Wu, Q. M., Zou, H. F., & Ma, J. Z. (2014). Nest site selection of white-naped crane (Grus vipio) at Zhalong National Nature Reserve, Heilongjiang, China. Journal of forestry research, 25(4), 947-952.

Based on the information above, I have decided to try enriching the niche of cranes by creating a hiding device, composed of familiar materials such as grass and reeds. However, providing a heap of plantation is redundant in a wild environment where cranes already care to reside; to go beyond this, an interactive element is needed.

Content and Form:

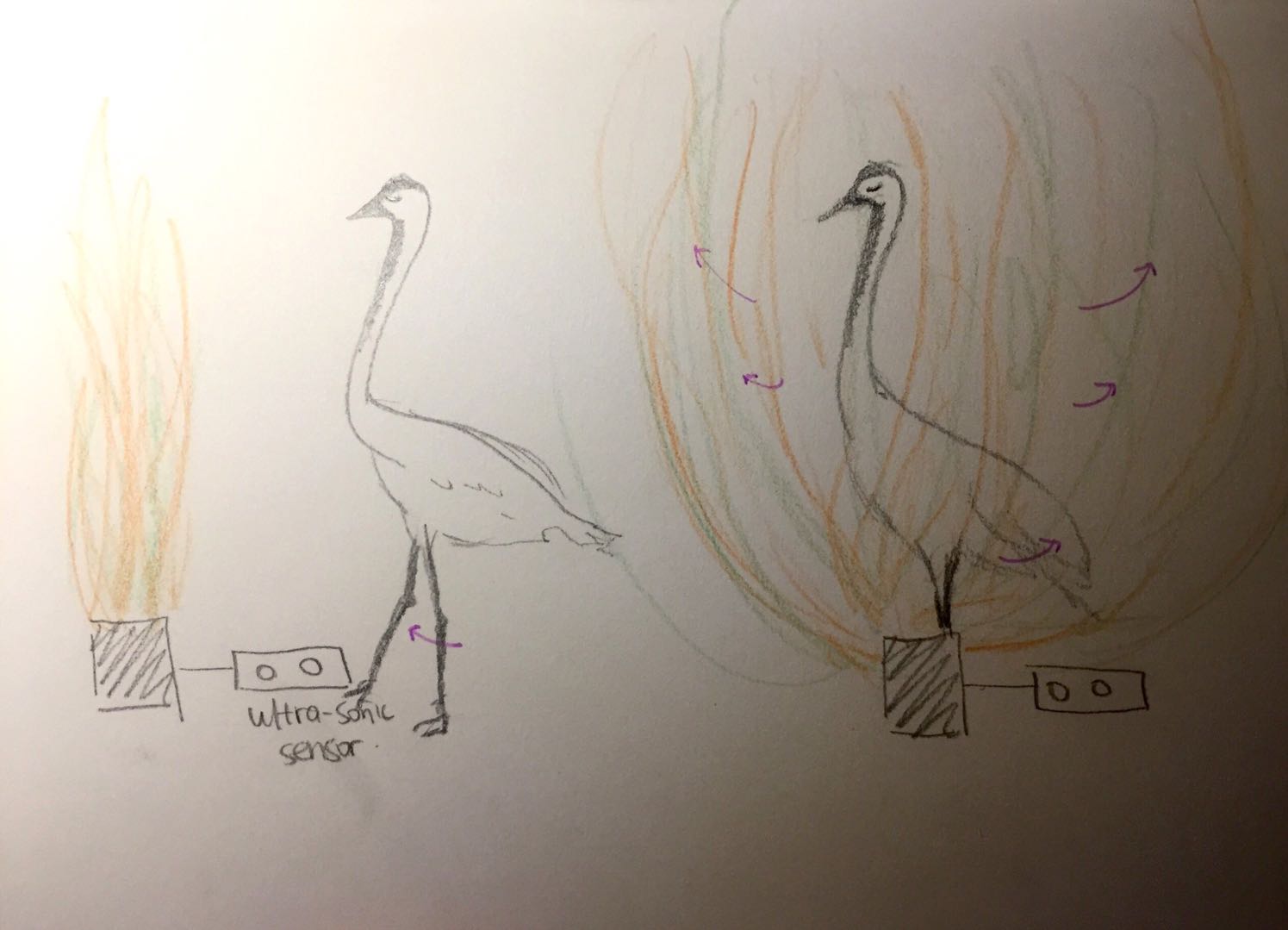

My idea is to design an installation where a heap of reed (which cranes like to select as roosting and nesting sites) will expand itself and become an ideal hiding space when an individual approaches towards an ultrasonic sensor. The expanded reed will close and return to its original shape when the crane distances itself from the device.

The expansive motion is inspired from the signalling dances that cranes exhibit, which frequently involve spreading of wings and rising of necks. Although the meaning of them are mixed depending on the circumstance and combination of postures, I postulate here that spreading motor activities are more likely to be attended by cranes since they have such social tendencies. This will make them react to the spreading and closing of grasses depending on their distance from the device, inviting interactions and even tentative communications.

Situation:

While literature suggests that cranes prefer to forage at open spaces and hide during nesting and roosting, the need to hide from predators might still persist during foraging, so in an ideal situation I would install the device at both open spaces and roosting sites, and compare the differences in cranes’ response to these two situations.

Possible additions:

In order to invite cranes to interact with the device, food might be placed among the grasses or social calls might be played from an external device hidden in the body. However, these are only suggestions and the impact on their behaviours and social recognition should be carefully assessed before implementation. It should also be designed with caution because the device’s purpose might become ambiguous when it serves as both a hiding site, a feeding station and a social experiment.

Stage 3: Making the prototype - How much pain does it take to create a form?

With substantial help from my designer fellows at this course, I decided to design my hiding device as the following layout:

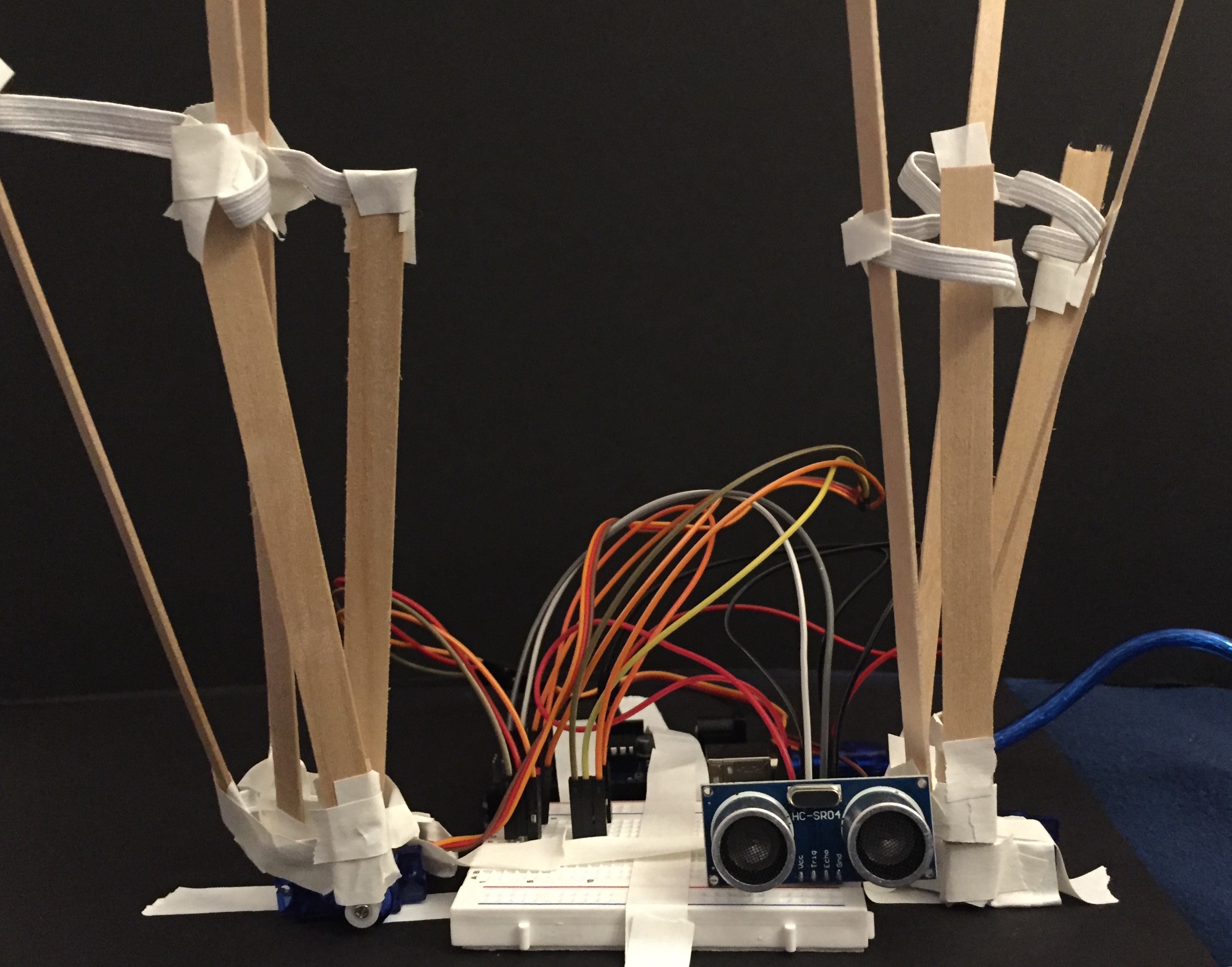

The ultra-sonic sensor’s position is fixed with a breadboard which will detect the distance of an object that directly faces it. By setting this I am assuming a unitary way of approaching from the individual crane, which is evidently unrealistic. However, for the current stage I decided this is as far as I can do.

I use a combination of wooden sticks and servo motors to create the expansion effect. My wooden sticks are put together in a fan-like structure, one end attached to the servo’s wing, which will unfold when the angle of the servo motor changes. The two servos are aligned in positions as shown to engender a fanning effect from the centre of the device towards the two ends, essentially widening the reeds for fuller coverage of the user’s sight.

I assume that cranes would not find wires and circuit boards the most appealing, so I cover the main circuit appearances with black foam board, which ideally should be made of natural materials such as turfs. Wooden sticks are poked on top to mimic reeds, assuming that in reality (is there a reality?) reed higher than the crane’s standing height would be planted on top of the device to attract attention and invite them to approach.

This is how the end-products look like. Please feel free to laugh at this:

I paid particular attention to present my device more than a circuit board, to give it a form and context. However, I completely overestimated my cutting skills, my artist tapes did not stick at all, I bought the wrong clothing pins so I had to use masking tapes over the black box, and in one of my testings I made some mistake with the code so that the servos kept spinning until they escaped from all the tapes, broke the sticks and ran towards freedom… I will do better next time.

Below is my Arduino code, which would not have happened without all the help I luckily received. It designates the servo to rotate from 0 to 90 when the ultrasonic sensor reads a distance smaller than 10 cm, and returns back to 0 when distance becomes bigger than 10 cm. To control the speed I introduced a global variable and some looping functions.

#include <Servo.h>

Servo servo1;

Servo servo2;

int pos = 0; // Variable to store the servo position

const int trigPin = 3; //connects to the trigger pin on the distance sensor

const int echoPin = 2;

float distance = 0;

void setup() {

// put your setup code here, to run once:

Serial.begin(9600);

servo1.attach(4);

servo2.attach(5);

pinMode(trigPin, OUTPUT); //the trigger pin will output pulses of electricity

pinMode(echoPin, INPUT);

}

void loop() {

// put your main code here, to run repeatedly:

int servoposition;

distance = getDistance(); //variable to store the distance measured by the sensor

Serial.print(distance); //print the distance that was measured

Serial.println(" in");

if (distance < 30)

{

servo1.write(pos);

servo2.write(pos);

delay(50);

if (pos <90){pos++; }

}

else

{

servo1.write(pos);

servo2.write(pos);

delay(50);

if (pos > 0){pos--; }

}

}

float getDistance()

{

float echoTime; //variable to store the time it takes for a ping to bounce off an object

float calculatedDistance; //variable to store the distance calculated from the echo time

//send out an ultrasonic pulse that's 10ms long

digitalWrite(trigPin, HIGH);

delayMicroseconds(10);

digitalWrite(trigPin, LOW);

echoTime = pulseIn(echoPin, HIGH); //use the pulsein command to see how long it takes for the

//pulse to bounce back to the sensor

calculatedDistance = echoTime / 148.0; //calculate the distance of the object that reflected the pulse (half the bounce time multiplied by the speed of sound)

return calculatedDistance; //send back the distance that was calculated

}

The majority of the code is from [Sofia’s] Empathy Machine - fox ear. It has also been a product of input from Fuad and Harpreet. Thanks!

Stage 4: Prototype testing via bodystorming - How was your experience at the Bird Hotel?

After hearing about my thoughts and witnessing my mental meltdown during coding and making, my user, the dedicated anthropologist who are going to pretend to be a crane, suggested me to call it a Bird Hotel.

Inspired by its name (and more importantly the time of the day), I stied to situate the testing at a time when the sun sets and the cranes would be looking for a site to roost and rest. Research has shown that cranes’ foraging and roosting activities are highly regular and align with sunrise and sunset:

Frith (1974) described one such roost of 30,000 birds that “filled the river”…In the morning, about 20 percent of the cranes typically leave the roost by sunrise, and nearly all are gone within 100 minutes after sunrise. In the evening, about 80 percent of the birds arrive back on the roost during the hour of sunset, and nearly all are on the roost by 40 minutes after sunset. Johnsgard, P. A. (1983). Cranes of the World: Demoiselle Crane (Anthropoides virgo).

I have also played a “wetland nature soundtrack” found on Youtube.

Since the reed is supposed to be taller than the crane’s standing height, it did not make much sense for my tester to approach the device with all of his body. Instead, he held a bird necklace handmade by himself, and explored the device with his hand.

Take a look at our testing video:

Stage 5: Future Iteration and Reflection - a dialogue with my tester

The first thing I heard from my tester after bodystorming is “very relaxing”:

The movement of the [reed]…it is very relaxing. It is slow, calm, and welcoming. But as an anthropologist I have to be critical of the bodystorming idea, of the assumption that mimicking animals can help us understand them. There is an over-valuation of the senses, trying to derive everything of the other from sensory perceptions, as if it is something empirical - if we can understand animal senses then we can understand their reality. That being said, I could relate to the movement as a test subject. I liked that movement.

I then talked with him about my worries of whether the cranes will behave towards the device as if it is a hiding site. We discussed the pattern of expanding reeds, the material used and the feasibility of the device in a natural environment:

S: I was not sure if they will recognise this as a bird hotel. A self-expanding heap of reed which moves as soon as you leave a certain range…they might not recognise something so ephemeral as an ideal hiding site.

V: Perhaps cranes are selective towards patterns of the grasslands, we just do not know. And also, even if the material is composed of real plantations, the movements might not align with the cranes’ knowledge of how nature and grass behaves, if we assume they have cognitive faculties. Anyway, this would not be something cranes are naturally used to.

S: I also thought the fact of there only being one ultrasonic sensor very unrealistic. There would be cranes approaching from different directions, and there will be other cranes hanging around near the device. If the device starts moving suddenly, it might scare the surrounding cranes.

V: Yes, the cranes may feel alienated if the reed moves too frequently, or if other cranes get scared. Maybe you can deal with that with more sophisticated sensors that sense multi-directional movements and can identify other cranes, so that the device is only activated when they are within certain distances, and also dependent on how many other cranes are present.

S: Maybe this motion can also be deployed for other functions, such as instead of a bird hotel, how about I swap the reed into feathers and create a social dancing machine? Since in their dances there are spreadings of wings. But just having feathers spreading out…would it not freak them out?

V: It may or may not. Do they like feathers? They might have a general liking towards feathers, let it be that of their own species or not. And the device doesn’t have to be in the shape of a crane. It might not freak them out.

S: Our project’s aim was to bring the concept of enrichment forward to wilderness, to build a conversation, or a dialogue. But with an animal, what is even a conversation?

V: I was just reading a book on interactive machines saying what they do with humans is not conversation but simply reading and writing; it’s a linguistic artefact. Now conversations with animals, which linguistic communication is not happening…having conversation with them? We tend to believe it’s sensory, but we don’t know. It could be philosophical. Or maybe they just like the patterns.

+Conclusion+

My dialogue with my crane tester ended with a period of silence, perhaps an awareness that we really do not know what a conversation with an animal means, that we really understand too little about animal’s reality. This moment comes with a sense of wonder, as I again realise how a design process as such pushes both the designer and the user to think and probe into the animal world.

While my empathy machine was extremely crude, did not take form into account at all, and I had to fill the user experience with my own narrations, this time I made an effort to let my device take a form, to mimic a heap of reeds, to cover up the circuits, to play a naturalistic soundtrack, and to test it by bodystorming. These led to more conversations about the user scenario that organically came from the tester himself, and a deeper discussion of the affects and functions of my device.

Regarding the prototype itself, it is interesting how it started from a functional purpose (a hiding place/a bird hotel) to a focus on the product’s form, the speed of movement, and how the user experience was essentially about observing the pattern itself rather than imagining its functionality. In some ways, it seems like a movement from enrichment towards a conversation.

Another take-away is to stop assuming the more naturalistic, the better. My tester pointed out that even if the materials look exactly like grass, the crane might still freak out because a machine-generated movement is not going to be like natural grass; if it does, then the technological intervention also loses its point. This makes me think what is human’s place in designing for animals. Assuming an absolute separation between human and nature, leaving the nature as it is, is clearly a non-starter for conceptualising design, nor is it a realistic standpoint in the anthropocene when human influence on the planet is omnipresent. What does it mean to intervene? Is building a conversation or dialogue a utopian effort? Where is the line between an attempt to speak and mere disruption?

I have no idea. But by attending to these making processes, reflecting on my research and imagining the universe of an animal, I would like to believe I am heading somewhere.